Usually proctoring (or invigilating in UK English) written exams at my university is a somewhat trying experience. Trying because I sit at the front of the classroom for over an hour in silence punctuated only by the frustrated sighing of my students. Looking out I see a sea of furrowed brows, scratched heads and, occasionally, expressions of total mental capitulation. The reasons for this are twofold. Firstly, students have quite often prioritized other studies (possibly including studying the effects of drinking and computer games on exam scores) over English and therefore aren’t especially well prepared for the exam. It’s important for me to recognize this as an examiner and to accept that I can’t write an exam that pleases everyone, especially those who don’t bother to prepare. However, the second reason for the atmosphere of general malaise in the exam room is that I am still far from a good writer of exams, and this is something that I would like to improve. This post will be a slightly self indulgent one (aren’t they all?) in which I have a look at what I did and what I can do better. I’m going to come back to this each time I write an exam to remind myself, and I’m putting it out there in case there’s anything to be learned from it for others.

Let’s start with the specifics. The worst question that I wrote on this exam (about a very common mistake) went like this:

Correct (수정) the underlined word in the sentence (1 point) and write it again on the line below using different language, but keeping the same meaning. (1 point)

3. I’m going on a date. I bought new shoes and jeans to look gentle.

This is fine as far as the first ‘(1 point)’, but then gets very confusing. So much so, in fact, that when grading the exam I misunderstood my own instructions and only marked the first part of the question and not the second. I was confused by students offering different versions of both of the word and sentence. There are two main problems here. The first is that the pronoun ‘it’ in the instructions could refer to either the word or the sentence, and here it’s more likely referring to the word. Largely this is just crap writing on my part, but it does also point to a wider issue that pronouns are an area of confusion for low level students and something that I should perhaps try to avoid in future.

The second problem here is that the instruction is not particularly clear anyway, especially if you’re reading the sentence on this blog. What I intended in writing the question was to challenge students to use a couple of other ways of expressing cause (“because I wanted to / so I would”), but without some form guidance it relies on students remembering the classroom context, and essentially turns the exam into a game of ‘guess what the teacher wants us to say’, which I would sincerely like my exams, and class in general, not to be. Next time I need to remember that it’s dangerous to rely on classroom context too much, and that anyone sitting down to take my exams should be able to supply the answers from a good knowledge of English.

While reflecting on this exam I wondered whether an example would have helped, but there was only one question of this type on the exam. It’s also very difficult to exemplify something like this without giving the answer away. However, I could have easily supplied a hint in the form of “because” and/or “so” as a prompt.

This is a general pattern in my exam writing. My question prompts tend to be too open, and this probably confuses students and also makes grading more difficult. Take these two examples:

Think of a movie that you saw recently. Write a sentence about parts of the movie. You must use some of the language that we used in class in each sentence.

Respond to these questions and give some helpful extra information.

Again, these are really hard to interpret without classroom context. What’s worse, in the first part, is that it doesn’t even call for successful or interesting use of the loosely defined “language we used in class”, but simply that it be used. This leads to answers like “his facial emotion is emotional”, which I feel like from the instructions deserves at least partial credit as we talked about emotional as a way to describe acting. The second instruction is a little bit better, but still requires much more clarity. What I wanted students to do was answer a yes/no question and supply a little bit more information in order to help the conversation to progress. Again this led to some strange answers that were difficult to grade. I also mixed some questions that followed on from each other with others that didn’t without really specifying which was which, and based following questions on expected answers to previous questions, answers which students didn’t give in some cases, making it impossible to answer the next question. On reflection the whole thing would have been much better set as a discourse completion task – something which would suit the conversation based nature of the class much better anyway.

These problems are symptomatic of a tension between language work and communication work that I often feel both in class and when writing exams. Largely my class is a conversation based one, with the emphasis on just saying something rather than saying something ‘correctly’. Prompts like the two under discussion here are an attempt to mirror that in an exam, but then they have to graded as such, and it’s difficult to know where to draw the line in terms of understanding or interest. Something which might go over fine between two students in conversation can look pretty senseless written down.

Basically, these prompts are me getting caught between assessing communication and assessing language (though I’d accept that there may not be a clear space between them in which to get caught). I either have to go one way or the other into a more open writing prompt with a rubric, or to more language based assessment; I can see plenty of good reasons not to do either. Asking my students to write extendedly in an exam seems unfair if we don’t do any writing in class*. On the other hand, a totally language knowledge based exam doesn’t seem to be in the spirit of the class, might require spending more time in class looking at language, and would probably be even more difficult than this exam was, as a lot of the marks that the students did get came from open prompts.

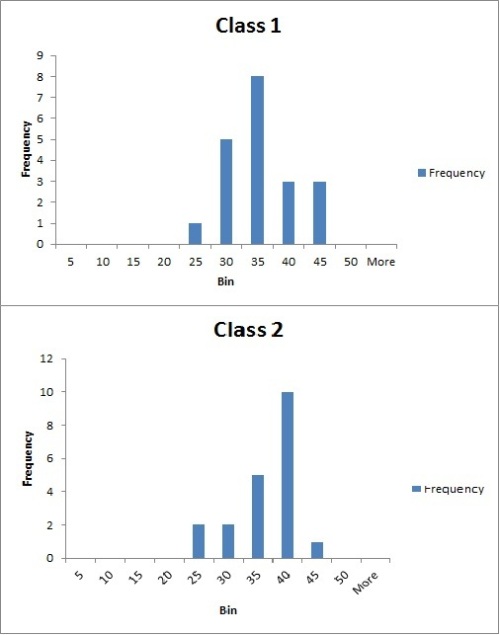

This I think is the last thing I want to talk about here, which is difficulty and grading. As I mentioned above, this exam was difficult for the students, as the two histograms below hint at.

On the diagram above, 5 refers to students scoring between 0 and 5 out of a maximum of 50. Bearing in mind that I work on around 90% being an A, and somewhere in the low 80%’s being a B, this exam left nobody getting an A and only 4 of 40 students getting a B. Honestly this is probably a-whole-nother blog post in itself, but clearly something is wrong here. Either the students are not learning what I think they are, or I am not giving them enough time in class to learn the stuff that I think is important, or they’re not learning full stop. When setting exams I’m definitely drawn to learning, and I hate setting questions about things that students should already know, but maybe that’s necessary to move the distribution up a bit. However I need to consider the kind of effect that it might have on students – will these marks give them a bit of a kick up the arse, or will they shatter the confidence that I had done pretty well at building up over the semester? Perhaps it might be a good time to collect some feedback?

I think I’ve got almost as far as I’m going to get with this post, but I’d welcome any thoughts anyone has on this, as I feel like I’ve made a little progress here, but there’s still some way to go. As a final bonus, here’s some other things that I need to think about next time:

- Using the British “maths” leads to all sorts of subject-verb agreement horrors.

- Be careful when using “repeat” if I really mean “rephrase”.

- How important is spelling? Is “claims” an acceptable attempt at “clams” if I tend to de-emphasise the importance of spelling. How about “cramps”?

- How can I make listening questions more difficult. Could I think about speaking faster or using a different accent?

Cheers,

Alex

* Although if the rubric assessed students in a similar way to our classwork (eg. content, understandability, interest) I guess it wouldn’t be so bad.

Aftern many semesters of experiences like the above, I always do three things with exams. 1. I always do the test myself before pressing ‘print’. Often I find that my points system doesn’t match the total I think it should be or some questions are too vague and can get answers I didn’t anticipate. 2. Always explain clearly in the class before what the test will consist of and give practice in each of the sections so they know exactly what is coming. 3. I know a lot of people out there will disagree but for Freshmen I give tests that anyone who puts in a hour or two’s prep can get a good score in. Only the lazy will not do well. This is because of point 2. above. If you don’t skip that exam prep class, you will know exactly how to prepare and where to look for the info you need.

Final point – I hate tests as much as my students and I make the midterm and final only 15% each of the total. Most of my grade goes on the completion of tasks and projects that are personal and meaningful to them:) Good blog post:)

Hi Mike,

Thanks very much for reading and taking the time to try and help. I really appreciate it.

I’ll certainly be taking your advice on point 1. I intended to this time, but my admin insists on having the exams early so they can proof them (but didn’t catch any of these problems of course), and I was really rushed. I’m totally with you on 2 and 3, and especially 3 was what I set out to do, but I seem to have miscalibrated my degree of difficulty sensor. Fortunately my school also has 15% for midterms and 15% for finals, and only 50% of those is writing, so even if they do mess it up it doesn’t affect their grade too badly.

Cheers again

Alex

As with any form of test or survey, it is always good to trial these. You could do this yourself (as Mike mentioned) or you could get your co-teacher to help you out with it. It is also important to know what your marking yardstick is to be and keep this very transparent otherwise you will start to get students coming back to you complaining about their marks.

Anyhow, I would reiterate what Mike mentioned. He has some very important and invaluable advice. When assessing more objective forms, such as speaking, it is really your own opinion which is the yardstick but it is good to create a template for speaking assessment which you could fall back on and perhaps relate it to the Common European Framework.

A wonderful blog post and very useful. You have to give a certain degree of leeway with examinations as long as it is justified but don’t make it a habit or you will get a barrage of questions and queries from students or your co-teachers. And don’t get me started on the Korean English test which assesses mostly translation and grammar.

Hi Martin,

Thanks very much for the comment.

Funnily enough I seem to get very few complaints about exams, which makes me wonder if I’m creating some of these problems in my own mind.

Speaking-wise I’m actually much more comfortable. I do have a clear rubric that I talk through with students, but the main thing is simply that it tests the things that we did in class. A written exam doesn’t really test this which is where I run into problems perhaps.

Trialling is definitely the way forward though.

Cheers,

Alex

Hi, great insights on written exams. Regarding listening questions, I teach IELTS listening. the harder parts are the ones that are more in academic context. That’s how you can make listening more difficult. Use more extracts from lectures. Have more academic language items. This could also be students talking about their course. Hope this helps.

Pingback: Collecting feedback on my exams | The Breathy Vowel

Pingback: Reflecting on my speaking exams | The Breathy Vowel

Instructions on an exam are important. It is good to bullet instructions that have parts. I recommend giving a sample where possible.

However, students (and people in general!) don’t read instructions. I usually give my students a mock test with only one or two items for each section, so they can see what the test will look like and what they are expected to do.

Working out the points properly ahead of time saves agony when checking the exams!

Worth investing time in this, you’ll be much more confident that the sighs belong to those that didn’t study!

Good luck!

Naomi

Hi Naomi,

Thanks for the advice. I actually did manage to do most of what you said above this time around, and I was pretty happy with the way the exams turned out. The trouble was it took AGES to create everything. I think I need to start putting together some questions banks. Anyway, it’s all done now and I can relax until next exam time.

Cheers,

Alex

Kudos!

It does get faster as you get more experienced and you should certainly reuse sections of previous exams!

Good for you!

Naomi